Exhibit 99.1

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF

DELAWARE

|

HEXION SPECIALTY CHEMICALS, INC.; NIMBUS

MERGER SUB INC.; APOLLO INVESTMENT FUND IV, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS

IV, L.P.; APOLLO ADVISORS IV, L.P.; APOLLO MANAGEMENT IV, L.P.; APOLLO INVESTMENT

FUND V, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS V, L.P.; APOLLO NETHERLANDS PARTNERS

V(A), L.P.; APOLLO NETHERLANDS PARTNERS V(B), L.P.; APOLLO GERMAN PARTNERS V

GMBH & CO. KG; APOLLO ADVISORS V, L.P.; APOLLO MANAGEMENT V, L.P.; APOLLO

INVESTMENT FUND VI, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS VI, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS

PARTNERS (DELAWARE) VI, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS (DELAWARE 892) VI,

L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS (GERMANY) VI, L.P.; APOLLO ADVISORS VI, L.P.;

APOLLO MANAGEMENT VI, L.P.; APOLLO MANAGEMENT, L.P.; and APOLLO GLOBAL

MANAGEMENT, LLC,

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

C.A. No. 3841-VCL

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

CONFIDENTIAL – FILED UNDER

|

|

)

|

SEAL

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

Plaintiffs,

|

)

|

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

v.

|

)

|

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

HUNTSMAN CORP.,

|

)

|

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

Defendant.

|

)

|

|

YOU ARE IN POSSESSION OF A DOCUMENT

FILED IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE THAT IS CONFIDENTIAL

AND FILED UNDER SEAL

IF YOU ARE NOT AUTHORIZED BY COURT ORDER TO VIEW OR RETRIEVE THIS DOCUMENT, READ NO FURTHER

THAN THIS PAGE. YOU SHOULD CONTACT THE

FOLLOWING PERSON(S):

|

|

|

Bruce L. Silverstein (#2495)

|

|

OF COUNSEL:

|

|

Rolin P. Bissell (#4478)

|

|

|

|

Christian Douglas Wright (#3554)

|

|

Harry M. Reasoner

|

|

Dawn M. Jones (#4270)

|

|

Texas State Bar No. 16642000

|

|

Kathaleen McCormick (#4579)

|

|

David T. Harvin

|

|

Tammy L. Mercer (#4957)

|

|

Texas State Bar No. 09189000

|

|

Richard J. Thomas (#5703)

|

|

VINSON & ELKINS L.L.P.

|

|

YOUNG CONAWAY STARGATT

|

|

First City Tower

|

|

&

TAYLOR, LLP

|

|

1001 Fannin Street

|

|

The Brandywine Building

|

|

Suite 2500

|

|

1000 West Street, 17th Floor

|

|

Houston, TX 77002-6760

|

|

Wilmington, DE 19801

|

|

(713) 758-2222

|

|

(302) 571-6600

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dated: September 2, 2008

|

|

Attorneys for Defendant, Counterclaim

Plaintiff

|

|

Corrected: September 4, 2008

|

|

|

Huntsman’s Pretrial Brief

THIS DOCUMENT IS CONFIDENTIAL AND FILED UNDER

SEAL.

REVIEW AND ACCESS TO THIS DOCUMENT IS

PROHIBITED EXCEPT BY PRIOR COURT ORDER.

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF

DELAWARE

|

HEXION SPECIALTY

CHEMICALS, INC.; NIMBUS MERGER SUB INC.; APOLLO INVESTMENT FUND IV, L.P.;

APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS IV, L.P.; APOLLO ADVISORS IV, L.P.; APOLLO

MANAGEMENT IV, L.P.; APOLLO INVESTMENT FUND V, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS

V, L.P.; APOLLO NETHERLANDS PARTNERS V(A), L.P.; APOLLO NETHERLANDS PARTNERS

V(B), L.P.; APOLLO GERMAN PARTNERS V GMBH & CO. KG; APOLLO ADVISORS V,

L.P.; APOLLO MANAGEMENT V, L.P.; APOLLO INVESTMENT FUND VI, L.P.; APOLLO

OVERSEAS PARTNERS VI, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS (DELAWARE) VI, L.P.;

APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS (DELAWARE 892) VI, L.P.; APOLLO OVERSEAS PARTNERS

(GERMANY) VI, L.P.; APOLLO ADVISORS VI, L.P.; APOLLO MANAGEMENT VI, L.P.;

APOLLO MANAGEMENT, L.P.; and APOLLO GLOBAL MANAGEMENT, LLC,

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

C.A. No. 3841-VCL

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

CONFIDENTIAL – FILED

|

|

)

|

UNDER SEAL

|

|

)

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

Plaintiffs,

|

)

|

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

v.

|

)

|

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

HUNTSMAN CORP.,

|

)

|

|

|

|

)

|

|

|

Defendant.

|

)

|

|

DEFENDANT

HUNTSMAN CORP.’S PRETRIAL BRIEF (CORRECTED)

|

OF COUNSEL:

|

|

Bruce L. Silverstein (#2495)

|

|

|

|

Rolin P. Bissell (#4478)

|

|

Harry M. Reasoner

|

|

Christian Douglas Wright (#3554)

|

|

Texas State Bar No. 16642000

|

|

Dawn M. Jones (#4270)

|

|

David T. Harvin

|

|

Kathaleen McCormick (#4579)

|

|

Texas State Bar No. 09189000

|

|

Tammy L. Mercer (#4957)

|

|

VINSON & ELKINS L.L.P.

|

|

Richard J. Thomas (#5703)

|

|

First City Tower

|

|

YOUNG

CONAWAY STARGATT

|

|

1001 Fannin Street

|

|

& TAYLOR, LLP

|

|

Suite 2500

|

|

The Brandywine Building

|

|

Houston, TX 77002-6760

|

|

1000 West Street, 17th Floor

|

|

(713) 758-2222

|

|

Wilmington, DE 19801

|

|

|

|

(302) 571-6600

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dated: September 2, 2008

|

|

Attorneys

for Defendant, Counterclaim Plaintiff

|

|

Corrected: September 4, 2008

|

|

|

Alan S. Goudiss

Jaculin Aaon

SHEARMAN & STERLING LLP

599 Lexington Avenue

New York, NY

10022

(212) 848-4000

Kathy D. Patrick

Jeremy L. Doyle

Laura J. Kissel

Laurel R. Boatright

GIBBS & BRUNS, L.L.P.

1100 Louisiana, Suite 5300

Houston, TX 77002

(713) 650-8805

DATED:

September 2, 2008

CORRECTED:

September 4, 2008

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

|

i

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE

OF AUTHORITIES

|

v

|

|

|

|

|

PRELIMINARY

STATEMENT

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

STATEMENT

OF FACTS

|

5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A.

|

Until

May 2008, Apollo Touts the Value of the Combined Entity.

|

5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B.

|

Apollo and Hexion

Decide To Abort the Merger Agreement.

|

7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C.

|

Apollo Orchestrates

D&P’s Opinion for Litigation Purposes.

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

|

Apollo Carefully

Controls the Process To Achieve Its Litigation Purpose.

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

|

D&P Is Denied

Access to Huntsman for Its “Insolvency” Opinion.

|

11

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.

|

Apollo Asks D&P

To Take the Unprecedented Step of Issuing an “Insolvency Opinion.”

|

12

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.

|

Apollo and Hexion

Spring D&P’s “Insolvency Opinion” and This Lawsuit on Huntsman Without

Warning.

|

13

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D.

|

The Publication of

the D&P Report Was Designed To Frustrate Consummation of the Merger.

|

14

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

|

The Banks That

Provided the Commitment Letter Had Never Before Been Concerned with Solvency

Until They Received a Copy of the D&P Insolvency Opinion.

|

14

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

|

The Insolvency

Opinion Impaired Hexion’s Ability To Obtain a Fair Price for Its Divestitures.

|

15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.

|

Hexion’s Reported

Attempt To Raise “Alternate Financing” Rather Than Supplemental Financing, Is

a Charade.

|

16

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.

|

Hexion Has Rejected

Supplemental Financing.

|

18

|

|

|

|

|

|

ARGUMENT

|

19

|

|

|

|

|

|

I.

|

Hexion’s

Failure To Consummate the Financing and Merger on the Grounds of “Insolvency”

Would Constitute a Breach of Hexion’s Covenants Under the Merger Agreement.

|

19

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A.

|

Hexion Is Not

Excused from Its Contractual Obligations Based on D&P’s “Insolvency

Opinion” Because Hexion Has Not Used Its Reasonable Best Efforts To Satisfy

the Conditions of the Commitment Letter and Has Failed To Keep Huntsman

Apprised of Material Events.

|

22

|

i

|

|

|

1.

|

The Merger

Agreement Imposes Stringent Obligations on Hexion To Consummate the Merger.

|

23

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

|

Hexion Has Blatantly

Breached These Obligations.

|

26

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a.

|

The Procurement of

an “Insolvency Opinion” Constitutes a Breach.

|

26

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.

|

Hexion’s Failure To

Keep Huntsman Informed Concerning the Status of Financing and Give Notice to

Huntsman Regarding Its Concerns About Financing Constitutes a Breach.

|

28

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B.

|

Hexion Has Breached

Its Obligation To Seek Supplemental Financing.

|

30

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C.

|

Had Hexion Used Its

Reasonable Best Efforts and Complied with Its Other Contractual Obligations,

It Could Obtain a Solvency Opinion or Deliver the Requisite CFO Certificate.

|

32

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

|

Contrary to

D&P’s Conclusion, There Is a Funding Surplus at Closing.

|

33

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a.

|

D&P Overstates

Amount Needed To Purchase Equity and Refinance Debt.

|

33

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b.

|

D&P Overstates

Upfront Pension Funding Obligations.

|

34

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i.

|

Hexion Ignored the

Advice of Their Regular Consultant.

|

35

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ii.

|

Apollo/Hexion

Retains a New Consultant To State that the PBGC Would Take a Stance Contrary

to Every Then-Current Indication from the PBGC.

|

36

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

c.

|

Fees and Expenses

Are Overstated.

|

38

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d.

|

Hexion Underestimates

Future Cost Synergies.

|

39

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

|

The Projections

Relied Upon by D&P Are Artificially Depressed and Inconsistent with

Huntsman’s Projections, Which Are Reasonable and Must Be Considered.

|

40

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.

|

The Combined Entity

Has Sufficient Capital To Pass the Capital Adequacy Test.

|

42

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.

|

D&P’S

Conclusion Is Undermined By Apollo’s Prior Analysis Valuations of the

Combined Entity.

|

44

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

II.

|

Huntsman

Has Not Suffered a Material Adverse Effect Under the Merger Agreement.

|

46

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A.

|

Summary of Argument.

|

47

|

ii

|

|

B.

|

MAE Provisions Are

Narrowly Construed as a Backstop Protecting Buyers from The Occurrence Of

Unknown Events, Not as an “Easy Out” or as Leverage For Buyers Seeking To

Renegotiate.

|

52

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C.

|

Huntsman Has Not Experienced

an MAE as Defined by The Merger Agreement.

|

55

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

|

Considering

Huntsman’s Business as a Whole, as Required by the Merger Agreement,

Huntsman’s Financial Performance Since Signing Is Consistent with Its

Historical Performance.

|

55

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a.

|

Huntsman’s

Post-Signing Financial Performance Is Consistent With Its Historical

Performance.

|

55

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i.

|

Huntsman Has Not

Suffered an Unusual Deterioration In Performance Since The Merger Agreement

Was Signed.

|

56

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ii.

|

Any Decline In

Huntsman’s Performance Is Not Long-Term.

|

57

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

iii.

|

Any Decline in

Huntsman’s Financial Performance Or Condition Is Attributable To General

Economic and Chemical Industry Conditions and Is Thus Carved-Out From the

Definition of an MAE in the Merger Agreement.

|

58

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b.

|

The Core Businesses

of Huntsman Are Strong and Growing.

|

62

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i.

|

Polyurethanes Is

Huntsman’s “Crown Jewel.”

|

62

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ii.

|

Performance Products

Is Outperforming Its Peers.

|

65

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

iii.

|

The Advanced

Materials Division Is Performing at Levels Consistent with Its Peers, and

Better Than Hexion.

|

66

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D.

|

Plaintiffs’ MAE

Contentions Are Inconsistent With the Merger Agreement and Their Extensive

Knowledge of the Conditions, Pre-Signing, That Have Been Responsible,

Post-Signing, for the Poor Performance of Huntsman’s TE and Pigments

Divisions.

|

67

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.

|

Huntsman’s Missed

Projections and Downward Revisions of Forecasts Cannot, Under The Terms Of

The Merger Agreement, Constitute an MAE.

|

67

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

|

The Financial

Performance of TE and Pigments, Like Their Competitors, Has Suffered for the

Same Reasons Known to Apollo Before Signing the Merger Agreement.

|

69

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

iii

|

|

|

a.

|

There Has Been No

Change in Huntsman’s TE Business Since Signing.

|

69

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i.

|

Plaintiffs

Well-Understood, Before Signing the Merger Agreement, the Challenges Facing

TE.

|

70

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ii.

|

The Restructuring

of TE Can Reasonably Be Expected To Significantly Improve Its Future Earnings.

|

71

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

iii.

|

TE Has Successfully

Implemented Significant Price Increases Without Losing Significant Sales

Volume.

|

72

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b.

|

Apollo Fully

Appreciated the Risks and Challenges Inherent in Both the Pigments Industry

Generally and Huntsman’s Pigments Business Specifically.

|

73

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

i.

|

Apollo Did Not View

Pigments as a “Core” Business Of Huntsman.

|

73

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ii.

|

Plaintiffs Wrongly

Contend That Huntsman Pigments’ Sulfate Production Process Represents a Major

Competitive Disadvantage.

|

75

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

iii.

|

After the Merger

Agreement Was Signed, Huntsman, and All Other Sulfate Process Producers,

Sustained an Adverse Impact from an Increase in the Cost of Sulfuric Acid,

Feedstock, and Energy.

|

77

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E.

|

Huntsman’s Current

Financial Condition Does Not Constitute an MAE.

|

78

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F.

|

Huntsman’s Decline

in Value and Share Price Since the Merger Agreement Cannot Constitute an MAE.

|

80

|

|

|

|

|

|

III.

|

Huntsman’s

Board Properly Extended the Merger Agreement.

|

81

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONCLUSION

|

85

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

|

|

|

Page

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cases

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Allegheny

Energy, Inc. v. DQE, Inc.,

|

|

|

|

74 F. Supp. 2d 482 (W.D. Pa. 1999)

|

|

54, 69

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bloor v. Falstaff

Brewing Corp.,

|

|

|

|

601 F.2d 609 (2d Cir. 1979)

|

|

24

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consolidated

Edison, Inc. v. Northeast Utils.,

|

|

|

|

249 F. Supp. 2d 387 (S.D.N.Y. 2003)

|

|

54

|

|

|

|

|

|

Doft & Co.

v. Travelocity.com Inc.,

|

|

|

|

No. Civ. A., 2004 WL 1152338 (Del. Ch.

May 20, 2004)

|

|

41

|

|

|

|

|

|

DynCorp. v. GTE

Corp.,

|

|

|

|

215 F. Supp. 2d 308 (S.D.N.Y. 2002)

|

|

54

|

|

|

|

|

|

Energy Partners,

Ltd. v. Stone Energy Corp., No. Civ. A. 2402-N, 2006 Del. Ch. LEXIS

|

|

|

|

182 (Del. Ch. Oct. 30, 2006)

|

|

22

|

|

|

|

|

|

Esplanade

Oil & Gas, Inc. v. Templeton Energy Income Corp.,

|

|

|

|

889 F.2d 621 (5th Cir. 1989)

|

|

54

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frontier Oil Corp.

v. Holly Corp.,

|

|

|

|

No. Civ. A 20502, 2005 WL 1039027

(Del. Ch. Apr. 29, 2005)

|

|

22, 47, 53

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hollinger

Int’l, Inc. v. Black,

|

|

|

|

844 A.2d 1022 (Del. Ch. 2004)

|

|

47

|

|

|

|

|

|

In re Emerging

Commc’ns Sh. Litig.,

|

|

|

|

No. Civ. A. 10415, 2004 WL 1035745

(Del. Ch. June 4, 2004)

|

|

40

|

|

|

|

|

|

In re

IBP, Inc. Shareholders Litig.,

|

|

|

|

789 A.2d 14 (Del. Ch. 2001)

|

|

22, 47, 52, 53, 54, 55, 69

|

|

|

|

|

|

In re Iridium

Operating, LLC,

|

|

|

|

373 B.R. 283 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2007)

|

|

32

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kroboth v. Brent,

|

|

|

|

625 N.Y.S. 2d 748 (N.Y. App. Div. 1995)

|

|

24

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moody v. Security

Pacific Business Credit, Inc.,

|

|

|

|

971 F.2d 1056 (3d Cir. 1992)

|

|

42

|

|

|

|

|

|

Northern Heel Corp.

v. Compo Indus., Inc.,

|

|

|

|

851 F.2d 456 (1st Cir. 1988)

|

|

54

|

v

|

Pan Am Corp. v.

Delta Air Lines, Inc.,

|

|

|

|

175 B.R. 438 (S.D.N.Y. 1994)

|

|

54, 69

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pegasystems, Inc.

v. Carrekar Corp.,

|

|

|

|

No. Civ. A. 19043-NC, 2001 WL 1192208

(Del. Ch. Oct. 1, 2001)

|

|

24

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pittsburgh

Coke & Chem. Co. v. Bollow,

|

|

|

|

421 F. Supp. 908 (E.D.N.Y. 1976); aff’d, 560 F.2d 1089 (2d Cir. 1977)

|

|

54

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rhone-Poulenc v.

GAF Chems.,

|

|

|

|

No. Civ. A. 12,848, 1993 Del. Ch.

LEXIS 59 (Del. Ch. Apr. 6, 1993)

|

|

22

|

|

|

|

|

|

SLC

Beverages, Inc. v. Burnup & Sims, Inc., 1987 Del. Ch. LEXIS 472 (Del. Ch. Aug. 20,

1987)

|

|

21

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vitalink Pharm.

Servs. v. GranCare, Inc.,

|

|

|

|

1997 Del. Ch. LEXIS 116 (Del. Ch.

Aug. 7, 1997)

|

|

20

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other Authorities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 E. Allen Farnsworth, Contracts § 7.17c (3d ed. 2004)

|

|

24

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bruce A. Markell, Toward True and Plain Dealing: A Theory of Fraudulent

|

|

|

|

Transfers Involving

Unreasonably Small Capital, 21 Ind. L. Rev. 469 (1988)

|

|

42

|

vi

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Apollo and

Hexion seek to terminate the July 12, 2007 Merger Agreement with Huntsman

that contains no financing condition, no exception to Hexion’s obligation to

use “reasonable best efforts” to complete the financing and the transaction,

and no right to terminate the contract absent a narrowly defined materially

adverse effect (“MAE”). Hexion, nonetheless, seeks a declaration that it has an

option to terminate because Huntsman’s business has suffered an MAE and because

the combined Huntsman-Hexion company (“Combined Entity”) would be insolvent.

The

illegitimacy of these claims is illuminated by the remarkably improper approach

Apollo and its sophisticated advisors have felt compelled to take. Although the

contract required consultation with Huntsman about any material activity

relating to financing and any change in Hexion’s good faith belief that

financing could be obtained, App. Tab A: JX-1, § 5.12(b),(1) the

first notice Huntsman received of alleged concerns was when it was sued. The

financing commitment required Hexion to promptly inform Credit Suisse and

Deutsche Bank (the “Commitment Banks”) if the projections furnished to them

were incorrect in any material respect and actively to assist the banks in

syndication efforts. Despite these provisions, the banks received their first

notice of alleged solvency concerns when Hexion filed suit. Cunningham Tr. at

114:25-115:2; 115:6-11; 117:7-15; Price Tr. at 270:9-22; 274:12-15.

Hexion

expressly warranted that the financing committed would be sufficient for it to

complete the transaction. App. Tab A: JX-1, § 3.2(e). Hexion is

obligated to use its reasonable best efforts to take all actions and do all

things necessary, proper or advisable to consummate the

(1) Exhibit references

refer to Trial Exhibits designated as Defendant’s Exhibits (DX) or Joint

Exhibits (JX). Citations will use the form “DX-xxxx” or “JX-xxxx” and will

provide pinpoint citations to the bates numbers appearing on the document when

possible. Selected exhibits are attached as an Appendix to this brief for the

Court’s convenience. References to Exhibits contained in the Appendix will use

the form “App. Tab [A]: DX-[xxxx], at [xxx].

1

financing, (including satisfying the conditions to the Commitment

Letter) App. Tab A: JX-1, § 5.12(a), to refrain from doing anything

that could reasonably be expected to materially impair, delay or prevent the

consummation of the financing, App. Tab A: JX-1, § 5.12(b), and to

consummate the transaction, App. Tab A: JX-1, § 5.13. Rather than

honoring its obligations, Hexion secretly hired litigation counsel who in

May 2008 retained a valuation firm, Duff & Phelps (“D&P”), as

“litigation experts.” D&P was advised

that the objective was to “get out” of the transaction. Pfeiffer Tr. at

67:19-68:5; DX-2256, at DUFF024355.

Before Apollo

and Hexion decided that they wanted to “get out” of the deal, Apollo had

already committed to cause its Funds IV and V to sell the Hexion-Huntsman

combination to Apollo Fund VI. Apollo arranged for that sale to occur pursuant

to fairness opinions – obtained as of February 25-26, 2008 – from

Valuation Research Corporation (“VRC”) for the selling funds and from Murray

Devine & Company (“Murray Devine”) for the buying fund. VRC concluded

that the combined entity of Hexion-Huntsman had an average enterprise value of

$15.5 to $17.1 billion. App. Tab S: DX-2664, at VRC 000971. In

March Apollo, acting as a fiduciary with respect to the inter-fund sale,

sent the fairness opinions of the two consulting firms plus Apollo’s own

valuation of $15.685 billion for the Combined Entity to the funds’

Advisory Boards. Apollo praised the prospects and benefits of the strategic

acquisition. App. Tab R: DX-2663, at APL 0502114.

Scarcely two

months later on May 9-12, 2008, Apollo conducted an in-house assessment,

doing elaborate studies and modeling. App. Tab P: DX-2495, at

APL 05500000, et seq. That

analysis demonstrated that the acquisition of Huntsman, while significantly

less profitable, provided a sound foundation for a solvency certificate. That

analysis showed, for example, “Potential Opportunities” through internal

actions to increase liquidity by approximately $1.1 billion. App. Tab P:

DX-2495, at APL 05500012.

2

Days later in

May, Wachtell brought “litigation experts” from D&P on board. After the

“litigation experts” had agreed to support completely the Apollo objective of

“getting out,” D&P coached its colleague Phil Wisler to give an “insolvency

opinion,” claiming that the combination of Huntsman and Hexion was worth some

$4.25 billion less than the $15.6 billion valuation Apollo previously had

given in its fiduciary capacity to its Funds. Contrast

App. Tab E: JX-598, at DUFF019282 with App. Tab R: DX-2663, at

APL05024114.

Prior to

obtaining the D&P “opinion,” Hexion never consulted with or advised

Huntsman of its concerns, as the Merger Agreement requires. Instead, it issued

a press release, delivered the opinions to the Commitment Banks, and sued

Huntsman, thereby knowingly and intentionally impairing the consummation of the

financing.

The Commitment

Banks had not expressed concerns about insolvency up to that point, even after

receiving Huntsman’s first quarter 2008 numbers. Cunningham Tr. at 97:10-15;

112:15-113:4; Price Tr. at 253:22-254:25; 270:18-22; 277:12-21. Each was

prepared to perform its financing commitment despite the fact that the terms

are below market and would cause multi-million dollar write-downs.(2)

Indeed, Deutsche Bank had been attempting to market a billion dollars of the

contemplated Hexion loan until it received the D&P “insolvency

opinion.” Cunningham Tr. at

111:10-112:6; 112:15-113:8.

Deutsche

Bank’s witness described Apollo’s actions as “out of the ordinary” and

“unique.” Cunningham Tr. at 121:2-12.

The banks were taken entirely by surprise. Id. at

118:14-21; Price Tr. at 270:9-22; 271:3-10. If Apollo and Hexion had believed

they had a

(2) As of April 2008,

the expected value of the loss upon funding to Deutsche Bank is XXXXXXXXXXX Cunningham Tr.

at 42:1-4; 42:24-43:5, Deutsche Bank has not terminated its funding commitment,

id. 58:24-59:2, and is prepared to fund

if the conditions of the commitment letter can be met at closing. Id. at 59:3-6. See also Price

Tr. at 275:9-20, “As of June 17, ...Credit Suisse was operating under the

assumption that a solvency certificate would and could be provided for the

combined company...[and] Credit Suisse was fully prepared, although it wasn’t

happy about it, to fund the commitment it had promised to fund under the

commitment letter.”); id. at 311:7-12

(Credit Suisse had embedded losses XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX under the financing commitment); and, at

293:10-18 (if solvency can be demonstrated in compliance with the commitment

letter, Credit Suisse today will “still perform its commitment.”).

3

legitimate and honest basis for claiming an MAE or insolvency of a

combination resulting from a merger, would they have felt it necessary to

breach Hexion’s contractual obligations and attempt to undermine the financing

commitments of the banks?

Apollo, having

made the decision that Hexion should “get out” of its contractual obligations,

has sought to do so by any means necessary. It has deliberately interfered not

only with the Merger Agreement, but with the Commitment Letter as

well.(3) Credit Suisse, unsurprisingly, has now embraced Apollo’s actions

as a means of avoiding XXXXXXXXXXX

XXXXX in mark-down

losses it will suffer if the Commitment is funded. Although it had never before

expressed any concern regarding the solvency of a combined Huntsman-Hexion

entity, Credit Suisse (acting at the behest of its litigation

counsel)(4) rushed to create its own “solvency analysis,” in the wake of

Hexion’s lawsuit. It is hardly surprising that Credit Suisse’s “analysis”

parrots D&P’s contrived “insolvency” opinion. But neither D&P’s

analysis nor Credit Suisse’s “analysis” can change this critical fact: before Hexion sued, no one

– not Hexion, not Apollo, not Credit Suisse, and not Deutsche Bank – had

expressed any concern that there had been an MAE

or that the combined entity would be insolvent.(5) That they do so now,

when each has buyer’s or banker’s remorse over their binding agreements, gives

every reason to doubt the credibility of their assertions.

And Apollo and

Hexion never confront the most fundamental problem with their efforts to

manufacture a solvency issue: the

specific and clear provisions of the Merger Agreement

(3) Cunningham Tr. at 117:18-118:13 (existence of lawsuit

complicates efforts to try to syndicate merger debt and is “probably not

helpful.”)

(4) Price Tr. at 294:18; 295:3-5 (explaining that Credit Suisse’s

“solvency analysis” was prepared “at the request” of Credit Suisse’s counsel).

(5) Cunningham Tr. at

97:10-15 (before suit was filed, Apollo never discussed insolvency with

Deutsche Bank); 119:2-11 (allegation of insolvency was “new information to

us”); 82:23-83:2 (Deutsche Bank has not concluded there has been a material

adverse event); and, 97:5-9 (before the lawsuit was filed, Apollo never discussed

whether there had been material adverse event at Huntsman); see also Price Tr. at 270:18-271:2 (prior to the lawsuit

Apollo had never said it had any concern the combined company would be

insolvent, or that they believed there had been a material adverse event as it

pertained to Huntsman).

4

itself. Under the agreement, there is no financing “out” and solvency

is not a condition to Hexion’s obligation to close. The declaration they seek –“

that Hexion is not obligated under the Merger Agreement to consummate the

merger if the combined company would be insolvent” – is not provided under the

terms of the Merger Agreement and is inconsistent with Hexion’s own

representations in the Merger Agreement. But the Merger Agreement is abundantly

clear that both Hexion’s failure to take any action or do anything about the

alleged “insolvency” and the efforts by Hexion and Apollo to establish

insolvency, and thus undermine the current financing, constitute a breach by

Hexion of the agreement and a tortious interference by Apollo.

We shall

demonstrate why the evidence and law confirm that Apollo and Hexion cannot meet

their burden of showing there has been an MAE – not even in general terms, much

less under the extremely narrow definition of MAE in the agreement – and that

Plaintiffs’ arguments that a satisfactory solvency certificate cannot be given

are meritless as well as irrelevant. Following trial, Huntsman requests that

the Court deny the relief requested by Apollo and Hexion and grant Huntsman the

relief it seeks in the Joint Pretrial Order, including an order of specific

performance against Hexion.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Until May 2008,

Apollo Touts the Value of the Combined Entity.

Apollo’s

“investment thesis” for acquiring Huntsman focused on the long-term prospects

for creating a “bellwether specialty chemical company” that would be a “must

own” in the specialty chemicals space and nearly double the size of

Rohm & Haas, the then-current bellwether stock. App. Tab Q:

DX-2662, at APL05028410. Based on this thesis, Apollo arranged for its

portfolio company Hexion to acquire Huntsman for $28 per share. App.

Tab A: JX-1. Apollo recognized that the deal had “high leverage,” but

believed it had obtained an

5

“aggressive structure” from the banks “to withstand most any potential

cyclical downturn.” App.

Tab Q: DX-2662, at

APL05028411.

In connection

with the transaction, Apollo proposed that Apollo Funds IV and V to sell their

equity interest in Hexion to Apollo Fund VI. Because the sale involved

conflicts of interest, Apollo was required to obtain the approval of the

Advisory Committees of the impacted funds to “ensure the fairness to investors

in each of the Apollo Funds.” DX-2188, at APL05024124-28. The proposed

inter-fund transfer was delayed, but Apollo again sought and obtained approval on

March 4, 2008. This is a critical date for purposes of this litigation. To

obtain that approval, Apollo co-founder Josh Harris distributed a detailed

packet of information to the Advisory Committees, which touted the value of the

Combined Entity and represented that it had an enterprise value of $15.685

billion. Id. at APL05024114. In support of the

proposed sale, Harris emphasized the benefits of the Combined Entity, noting:

Significant

Scale – The combination creates a $15.4 billion sales

and $2.1 billion EBITDA business on a pro forma basis. …

World-Class Management

Team – The combined company will be led by Craig

Morrison, the CEO of Hexion. Mr. Morrison and his team, together with the

best in class managers from Huntsman, will drive an immediate integration

strategy and share best practices. …

Significant

Near-Term Upside from Integration – … Apollo

management have conservatively estimated $250 million of synergies. …

Large Scale

with Potential for Value-Enhancing

Divestitures – The scale of the combined company will allow

management to selectively pare the portfolio to focus on the most strategic

business segments, while inherently enhancing margins. …

Ample Size

to Command Valuation Premium – Larger capitalization

chemicals companies command a 1-2 EBITDA multiple valuation premium in today’s

public equity markets. The combined company would be well positioned as one of

the largest specialty chemical company [sic] in the world, and is expected to

be valued at a large-cap premium multiple.

6

Id. at

APL05024126-27.

Also contained in the information packet were

two fairness opinions for the Apollo Funds from two reputable valuation

experts, Valuation Research Corporation (“VRC”) and Murray Devine. Id. at APL05024116-123.

Apollo supplied these experts with the “latest” and “most reasonable”

model and projections it had for the Combined Entity, which estimated the

enterprise value of the Combined Entity at $15.8 billion based on detailed

financial five-year financial projections.

Sambur Tr. at 140:10-16; 145:19-146:2; DX-2257. Using the information supplied by Apollo,

both firms opined that the proposed sale of Hexion would be fair to each of the

Funds, and VRC calculated an average enterprise value in excess of $16

billion. App. Tab R: DX-2663, at

APL05024120, APL05024122; App. Tab S: DX-2664, at VRC000971.(6) The

Advisory Committees approved the deal, which contemplates that Fund VI will pay

$1.151 billion for Funds IV and V interest in Hexion if the merger closes. App. Tab R: DX-2663, at APL05024126.

B. Apollo and Hexion Decide To Abort the Merger Agreement.

In April 2008, Huntsman reported

lower-than-expected earnings for the first quarter of 2008 due to rising energy

prices, higher raw materials costs, the decline in the value of the U.S.

dollar, and a slowdown in certain sections of the economy. Apollo’s Harris called Jon Huntsman and Peter

Huntsman and asked about the impact of foreign currency exchange rates, oil

prices, and U.S. economic conditions and what Huntsman was doing to mitigate

these impacts.

(6) In addition to

supplying models and other due diligence materials, the terms of VRC’s

engagement letter with Apollo required Apollo to “notify VRC with a reasonable

promptness upon discovery if any such information becomes inaccurate,

incomplete, or misleading” and to “notify VRC with a reasonable promptness upon

discovery of any material adverse change or development that could reasonably

be expected to lead to any material adverse change in its business properties,

operations, financial condition, or prospects.”

DX-2725; Rucker Tr. At 48:10-14; 49:22-50:2. The terms of the supplemental engagement to

update the fairness opinion in February was to state that the update can

be performed “[a]ssuming that the financial forecast has not changed from the

forecast used in the July 28, 007 opinion, and that there have been no

material adverse changes in Hexion, LLC, Huntsman Corporation, or the

industry.” DX-2729; Rucker Tr. at

122:16-22. As of February 26, 2008,

Apollo had not taken the position that a material adverse effect had occurred

in Huntsman’s business.

7

Huntsman Tr. at 257:25-259:12. Harris then instructed his team at Apollo to

re-analyze the proposed transaction and Apollo’s expected returns. From approximately May 6 to 12, 2008,

Apollo’s Scott Kleinman, David Sambur, and Jordan Zaken prepared an analysis of

the Combined Entity. Sambur Tr. at 192:3-198:17; App. Tab P: DX-2495. This analysis contained a variety of updated

Apollo models and projections, along with a spreadsheet tying those models and

projections to Apollo’s expected returns.

App. Tab P: DX-2495, at

APL05500027. None of these models and

projections showed that the Combined Entity would be insolvent. Id. at

APL05500029, APL05500044, APL05500059.

Two of the models reflected an entity with substantial positive cash

flows, while Apollo’s most negative model projected an entity with tight cash

flows. Id.

at APL05500034, APL05500059, APL05500064, and APL05500079. The analysis also identified more than $1

billion in opportunities to improve the Combined Entity’s liquidity, meaning

that Apollo identified numerous ways to keep the Combined Entity solvent. Id. at

APL05500059, APL05500027, and APL05500103.

More importantly to Apollo, the analysis

reflected that Apollo’s potential profit (or loss) and rates of return were at

risk of substantially decreasing. Id. at APL05500103.

Based on this analysis, Apollo determined to abort the Merger

Agreement. But even under the most

negative model, the terms of the Merger Agreement did not allow Hexion simply

to terminate the transaction. Therefore,

Apollo and Hexion contrived a plan to get out of the deal on the theory that

the Combined Entity would be insolvent and, thus, financing would be

unavailable. To execute the plan, Apollo

and Hexion turned to the litigation team at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen &

Katz (“Wachtell”). To support the claim

of insolvency, Wachtell engaged D&P and gave it limited and tailored

information prepared by Apollo to support an opinion that the Combined Entity

would be insolvent. Wachtell then

convinced D&P to render a novel but fatally flawed “insolvency” opinion

that Hexion promptly released to the public when filing this lawsuit.

8

C. Apollo Orchestrates D&P’s Opinion for Litigation

Purposes.

1. Apollo Carefully Controls the Process To Achieve Its

Litigation Purpose.

Despite Hexion’s obligation to use reasonable

best efforts to obtain a solvency

opinion, Apollo and its counsel carefully structured the engagement of D&P

to ensure that they would receive an opinion to support their claim that the

Combined Entity would be insolvent. To achieve this purpose, D&P’s engagement

was structured in two phases – (i) a “litigation consulting” phase and (ii) an

“opinion” phase. During the first phase,

D&P’s consulting agreement acknowledged, “We understand that we are being

retained . . . in connection with . . . the potential

litigation. . . .” See DX-2259, at DUFF036084.

For the second phase, the engagement letter envisioned retention of a

separate “opinion team” if “Hexion decides to go forward with a particular

cause of action.” See

Id., at DUFF036085.

It is clear that from the beginning D&P

understood that its role was to support Hexion’s effort to get out of the

Merger Agreement. Allen Pfeiffer, the

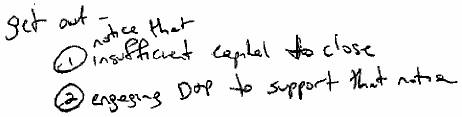

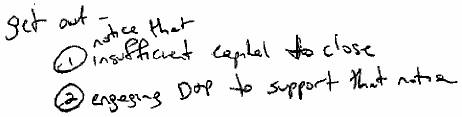

senior member of the D&P consulting team, memorialized the purpose of the

engagement in his handwritten notes on May 16, 2008:

ALLEN M.

PFEIFFER

MANAGING

DIRECTOR

TEL

973-775-8260 ·

FAX 443-601-2265

allen.pfeiffer@duffandphelps.com

DX-2256, at DUFF024355;

Pfeiffer Tr. at 67:1-68:23.

9

Accordingly, D&P’s consulting team began

searching for “any loopholes” or “wriggle room for Apollo to back out of the

deal.” App. Tab V: DX-2667, at

DUFF035627. To enable D&P to find

insolvency, Wachtell sent D&P a series of models showing (1) worse

projections for Huntsman and Hexion and (2) transactional expenses that

were higher than those Apollo had used in its modeling on May 9 and higher

than those used some two months earlier in the models shown to VRC and Murray

Devine, for purposes of obtaining their fairness opinions.

Not surprisingly, toward the end of May,

D&P’s consulting team concluded that the Combined Entity would be insolvent

and so advised Wachtell. Pfeiffer Tr. at

125:4-10, 126:4-9, 157:19-158:6. Only

after D&P’s consulting team had provided that conclusion, was D&P’s

opinion team allowed to proceed to phase two of D&P’s engagement. Prior to that time, D&P “didn’t want [the

opinion team] to be tainted or

impacted by our broader consulting advice.”

Pfeiffer Tr. at 81:8-10 (emphasis added). However, Phil Wisler, who led the opinion

team at D&P, was involved in the initial discussions with Wachtell about

this matter. See

DX-2711. He knew from the outset that if

the litigation consulting team reached a favorable conclusion for Apollo and

Hexion, then the opinion team would be engaged.

Pfeiffer Tr. at 81:21-82:3. By

having Hexion enter into a separate engagement with the D&P opinion team,

Apollo structured the process to create the public perception that D&P was

retained by Hexion’s Board of Directors for purposes other than providing an

opinion to support litigation. This fact

is evidenced by Hexion’s June 18, 2008 press release, which refers only to

the second engagement. DX-2318.

Not surprisingly, the opinion team did its

analysis in record time. On Friday, June 6,

Mr. Wisler pitched D&P’s qualifications to the Hexion Board “for three

minutes,” see DX-2712, and Hexion retained D&P

the same day. DX-2713. By Tuesday, June 10, the opinion team

submitted its draft opinion and analysis for review by an internal D&P

committee. By June 15,

10

D&P sent a draft solvency analysis and

opinion to Wachtell for review.

DX-2714. Three days later,

D&P presented to the Hexion board its “insolvency opinion.”

2. D&P Is Denied Access to Huntsman for Its “Insolvency”

Opinion.

Throughout its consulting and opinion work,

D&P never consulted with Huntsman about the solvency work it was

doing. Apollo, Hexion, and Wachtell

decided that D&P would not have access to Huntsman because, as Pfeiffer

testified, if they informed Huntsman of the engagement, it would “compromise

the objectives that were set forth by [Hexion’s] board.” Pfeiffer Tr. at 109:18-110:3.

Although witnesses from D&P, Apollo, and

Hexion offer various excuses for why D&P was not allowed access to

Huntsman, the importance of this fact cannot be understated. D&P’s opinion highlights this fact

noting, as a qualification and limiting condition, that it “[d]id not have

direct access to Huntsman management.”

App. Tab D: JX-597; see also App.

Tab E: JX-598. This limitation is

in contrast to D&P materials that identify the importance of having contact

with management as part of D&P’s due diligence. See DX-2709, at

DUFF026551. Yet Phil Wisler of D&P

claims that contacting Huntsman did not occur to him and that he did not know

how he would have responded if his client suggested that he do so, even though

this was a specific “limitation” and “qualification” to his opinion. Wisler Tr. at 141:20-142: 23; 146:3-11.

D&P’s failure to contact Huntsman is particularly

egregious given the novelty of the “insolvency opinion” D&P produced. Other valuation professionals with expertise

in issuing solvency opinions have testified that “[i]t’s important to get

management’s perspective on how the business is currently doing and what the

business’s future prospects are,” Rucker Tr. at 32:2-5, and that it is

important to get management’s views about the business because “[m]anagement

manages the business; therefore, they are in control of the cash flows,” Kenny

Tr. at 28:2-3. Plaintiffs try to justify

this failure by arguing simply that D&P did not consult with Huntsman

11

because Hexion’s projections for Huntsman

were sufficient, Morrison Tr. at 198:9-21, and that Hexion and Apollo were in a

position to be more “objective” about Huntsman’s business than Huntsman. Morrison Tr. at 199:13-21. But the evidence will show that the Hexion

projections furnished to D&P differed from those done just days earlier in

Apollo’s internal analysis and were designed to produce a finding of

insolvency.

3. Apollo Asks D&P To Take the Unprecedented Step of Issuing

an “Insolvency Opinion.”

The purpose of D&P’s engagement is also

revealed by the communications between Wachtell and D&P regarding what form

D&P’s final work-product should take.

During the week of June 9, 2008, D&P told Wachtell that the

D&P opinion team had reached an opinion as to the insolvency of the

Combined Entity. Pfeiffer Tr. at

225:12-226:22. At that time, it was not

clear what form D&P’s final product would take. Pfeiffer Tr. at 226:20-227:4. One idea was for D&P simply to state that

it was not in a position to issue an opinion of solvency. Pfeiffer Tr. at 230:1-12.

Wachtell and Apollo, however, asked D&P

to issue an opinion stating that the company was insolvent based on the

three traditional solvency tests.

Pfeiffer Tr. at 230:18-22. “Even

though … that is something that is somewhat more aggressive and … something

that – we haven’t done very often,” the D&P team finally “got comfortable”

with this concept. Pfeiffer Tr. at

230:23-231:6. Normally, D&P does not

issue an “insolvency opinion” or even a letter stating that it could not issue a solvency opinion. In those situations, the deal is changed or

terminated, or D&P does not move forward with its analysis. Pfeiffer Tr. at 31:2-31:9. In fact, no D&P witness could recall a

situation where D&P had ever issued an “insolvency

opinion” outside the context of litigation.

Pfeiffer Tr. 30:22-31:13; Turf Tr. 29:1-30:7; Wisler Tr. at

62:15-63:13. Likewise, neither of the

valuation professionals at VRC and Murray Devine who testified in this

12

case had ever

issued or even seen an “insolvency opinion.”

Rucker Tr. at 173:4-8; Kenny Tr. at 33:1-14.

4. Apollo and Hexion Spring D&P’s “Insolvency Opinion” and

This Lawsuit on Huntsman Without Warning.

On June 18, the plan that Apollo and

Hexion had put into place more than a month earlier culminated in three key

events. First, Hexion’s Board of

Directors met and received the formal written D&P insolvency opinion. Second, Hexion issued a press release

attaching the D&P insolvency opinion and claiming that the Merger could not

be consummated because (a) the combined company would be insolvent and the

banks, therefore, would not provide the financing contemplated under the

Commitment Letter, and (b) Huntsman had suffered a “material adverse

effect” as defined in the Merger Agreement.

App. Tab L: DX-2317. Third,

Apollo and Hexion filed their complaint in this action.

Apollo claims to have had “concerns” about

the solvency of the Combined Entity beginning in May. Kleinman Tr. at 165:17-167:19; Harris Tr. at

378:1-379:16; Zaken Tr. at 78:2-79:7.

But no one from Apollo or Hexion communicated those concerns to Huntsman

or sought to engage Huntsman in any dialogue about addressing the

concerns. Rather than work with Huntsman

or take the actions required under the Merger Agreement, Apollo and Hexion

retained litigation counsel, hired D&P to issue an insolvency opinion, and

prepared to file this lawsuit. Indeed,

the only notice Hexion ever gave Huntsman of its concerns about the adequacy

and availability of financing is a single phone call after this lawsuit

was filed, during which neither the litigation nor the press release was

discussed. Morrison Tr. at

234:10-235:20.

13

D. The Publication of the D&P Report Was Designed To

Frustrate Consummation of the Merger.

1. The Banks That Provided the Commitment Letter Had Never

Before Been Concerned with Solvency Until They Received a Copy of the D&P

Insolvency Opinion.

Hexion’s June 18, 2008 press release

announced that, based on the D&P opinion, it believed that the Combined

Entity would be insolvent and that, as a result, it did not believe “the banks

will provide the debt financing for the merger contemplated by the commitment

letters.” To ensure fulfillment of its

prophecy, Hexion then delivered the D&P opinion to Deutsche Bank and Credit

Suisse.

The D&P opinion came as a complete

surprise to the banks. Cunningham Tr. at

115:12-16, 119:2-11. Even after seeing

Huntsman’s first quarter financial results, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank did

not believe that the combined company was insolvent. Price Tr. at 96:6-14; Cunningham Tr. at

112:22-113:4; 119:2-11. Even though

Apollo had had several meetings with the banks in 2008, prior to June 18

Apollo had not advised the banks that the combined company would be

insolvent. Price Tr. at 270:18-22;

Cunningham Tr. at 119:2-20. The banks

had not concluded that the combined company would be insolvent and were

surprised to learn of D&P’s insolvency opinion. Price Tr. at 271:3-10; Cunningham Tr. at

97:10-15, 119:2-11. Prior to receiving the

D&P opinion, the banks were fully prepared to fund their commitments. Price Tr. at 275:15-20.

Of course, the banks changed their position

upon receipt of D&P’s insolvency opinion.

Price Tr. at 276:3-7, 16-20.

Since learning of the insolvency position, Credit Suisse has sought to

take advantage of D&P’s insolvency opinion by producing its own insolvency

analysis, which is essentially a copy of D&P’s work. Prior to June 18, Deutsche Bank was

actively trying to syndicate the financing for the deal; now Deutsche Bank has

ceased such efforts because D&P’s opinion was “not helpful.” Cunningham Tr. at 118:1-13.

14

2. The Insolvency Opinion Impaired Hexion’s Ability To Obtain a

Fair Price for Its Divestitures.

The potential merger of Hexion and Huntsman

raised antitrust concerns. Pursuant to

§ 5.4 of the Merger Agreement, the parties agreed to send notification to

antitrust regulators in the United States and European Union, to cooperate and

keep each other reasonably informed about information requested by and provided

to the regulators, and to use reasonable best efforts to ensure the prompt

expiration of any applicable waiting periods or the receipt of antitrust

approvals. App. Tab A: JX-1, §

5.4. Hexion also agreed to a “hell or

high water” clause that required it to take any and all actions necessary to

ensure that antitrust clearances were obtained.

App. Tab A: JX-1, § 5.4(b).(7)

In connection with the antitrust review

process, Hexion was advised that it would have to divest certain of its assets

to satisfy antitrust regulators. To

comply with this requirement, Hexion hired a third party, KeyBanc Capital

Markets (“KeyBanc”), to identify potential buyers for the assets obtain bids

from them to acquire the divested assets subject to completion of the

merger. KeyBanc began communicating with

potential bidders in late April or early May 2008 and receiving

initial indications of interest from bidders on May 21, 2008. DX-2715 at MLB003405. The initial indications of interest from

eleven bidders ranged in value from $160 to $405 million. App. Tab J: DX-2268. Seven of these bidders were invited to attend

management presentations and submit final bids in late June. DX-2715, at MLB003407.

The expectation of receiving high bids to

acquire these assets was quickly dashed.

On June 18, at the request of Apollo, KeyBanc sent a letter to all

bidders informing them of the lawsuit.

App. Tab K: DX-2314. While

nominally stating that the filing of the lawsuit did not “end” Hexion’s

obligations related to divesting a copy of Hexion’s press release, which stated

(7) Hexion has not moved

promptly and is still awaiting antitrust clearance in the United States, but it

may still obtain clearance before the merger is consummated. Huntsman believes that the process has been

deliberately delayed as a tactical maneuver to delay the closing obligations of

Hexion.

15

that Hexion no longer believed the Combined

Entity would be solvent and that D&P had issued an opinion to the same

effect. Id.; see

also Schneir Tr. at 224:12-225:3; 225:11-19; 226:9-227:1. After receiving this letter, four of the six

remaining bidders dropped out of the process.

Several bidders cited the filing of the lawsuit as a factor in their

decision not to go forward. Only the two

lowest bidders remained. Schneir Tr. at

236:11-19; 237:16-24; 238:5-239:20; 272:10-273:13. Not surprisingly, the final bids from these

two bidders were substantially lower than the two highest initial indications

of interest and Hexion accepted a bid that was approximately $250 million less

than the highest initial bid, which it also provided within the range of

possible bids to the FTC. App.

Tab J: DX-2268.

3. Hexion’s Reported Attempt To Raise “Alternate Financing”

Rather Than Supplemental Financing, Is a Charade.

Hexion is obligated to use its reasonable

best efforts to consummate the Merger.

Merger Agr., § 5.13(a). If

there were a legitimate solvency problem, Hexion would be required to seek

supplemental financing or equity to solve that problem. See App.

Tab A: JX-1, § 5.12(a), 5.13(a).

Moreover, Hexion is required to use “reasonable best efforts” to obtain

alternate financing only if the financing contemplated by the Commitment Letter

fails for some reason. See id.,

§ 5.12(c). The Commitment Letter

has not failed. Both banks have stated

that they will fund if the condition requiring a solvency certificate/opinion

is satisfied. Cunningham Tr. at 59:3-6;

Price Tr. at 293:10-18.

Hexion has pleaded that it will continue to

use its reasonable best efforts to close the transaction, but it has also

pleaded that it does not believe that alternate financing will be

available. Hexion has gone through the

motions of seeking alternate financing, which it knows would not be available

on the same terms as those provided in the Commitment Letter, but Hexion has

deliberately refused to consider additional or supplemental

financing, if required, to close the merger.

16

Hexion hired Gleacher Partners on July 15,

2008 to assist in seeking financing, but Hexion has limited Gleacher (1) to

soliciting only alternate financing, i.e., financing

that would completely replace the existing financing, and (2) to

soliciting such alternate financing on the same or better terms than those

provided by the Commitment Letter.

Tepper Tr. at 24:23-25:23.

Gleacher has suggested that it might be possible to find “additional

financing” (i.e., supplemental financing) to bridge

any funding gap, but Apollo has instructed Gleacher that its mandate does not

include looking into other ways to “complete the financing.” Tepper Tr. at 54:22-55:8; see also App. Tab W: DX-2668, at GLCH 2333.

Gleacher’s representative testified that, before Apollo retained Gleacher, he advised Apollo that it

would be impossible to obtain alternate financing under the same terms in the

current market without changing the structure of the financing:

The advice at the time that I gave Apollo/Hexion was that it would be extremely

difficult, and furthermore we would need to find a party who would be willing

to do something uneconomic in order to make the financing package work in this

market. So straight

up it would be impossible.

Tepper Tr. at 50:14-51:29

(emphasis added). Despite this advice,

Apollo limited Gleacher to obtaining financing on the same terms provided in

the 2007 Commitment Letter, without changing the structure of the

transaction. And Hexion has paid

Gleacher $1 million to undertake this impossible task regardless of whether

Gleacher is successful. Tepper Tr. at

28:4-10.

Apollo’s own involvement in the Gleacher

process demonstrates that the process was a sham. Gleacher is an independent investment bank,

presumably with solid relationships at numerous institutions. Yet Apollo vetted Gleacher’s suggested list

of potential funders, reducing the list to institutions that already had a

relationship with Apollo or Hexion.

After thus limiting Gleacher’s approved contact list to seven

institutions – including Bank of America, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, Goldman

Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and, oddly enough, Credit Suisse and Deutsche

17

Bank – Apollo provided Gleacher with a list

of Apollo’s contacts at the banks, rather than allowing Gleacher to use its own

contacts at those institutions. Tepper

Tr. at 65:8-14. And, before Gleacher

could even have its first conversation with those contacts, Apollo also called

them first, providing them with Apollo’s own spin on the transaction. Tepper Tr. at 60:18-24. Not surprisingly, none of the banks

pre-screened and contacted by Apollo was interested in providing alternate

financing. Tepper Tr. at 75:22-25.

4. Hexion Has Rejected Supplemental Financing.

Despite the efforts of Apollo and Hexion to

sabotage the deal, there are parties who are interested in helping finance the

merger. Huntsman, Hexion, and Apollo

have all received unsolicited offers for additional financing from parties that

are interested in seeing the merger close.

See Esplin Tr. at 346:38, 348:3-11;

Kleinman Tr. at 242:14-243-6; Tepper Tr. at 63:21-64:10. Several large equity and debtholders of

Huntsman have come forward with offers to provide funds that would bridge any

alleged funding gap – expressing an interest in providing up to $1 billion in

additional funds. Tepper Tr. at

112:22-113:3. For example, Matlin

Patterson, GLG Partners, and D.E. Shaw have all expressed an interest in

supplying equity for the combined company, putting funds in escrow to meet cash

flow shortfalls and other solutions to facilitating the deal in other

ways. Tepper Tr. at 85:21-86:10. But Apollo has refused to let Gleacher

negotiate with parties that might provide additional funding to ensure that the

merger is completed. According to the

testimony of Gleacher’s representative, when Gleacher relayed to Apollo

suggested options for closing the deal, Apollo instructed him that Gleacher’s

mandate was “not to pursue a change in the merger agreement” but “to pursue

alternate financing.” Tepper Tr. at

88:23-89:10; App. Tab W: DX-2668, at GLCH 2333.

Hexion has also rejected – and ordered

Gleacher to reject – offers from third parties to provide supplemental

financing. On August 28, 2008,

several large, independent shareholders of

18

Huntsman delivered a letter to Hexion and

Apollo indicating their willingness with other shareholders to commit to

purchase at least $500 million of Contingent Value Rights (“CVRs”) to be issued

by Hexion upon consummation of the merger.

See DX-2385. The terms of the CVRs would enhance Apollo’s

value in the post-merger Hexion, supplement post-merger liquidity, and

effectively reduce Hexion’s “day one” funding obligation by approximately $500

million. Hexion rejected the offer in

about two hours, issuing a press release stating that the “proposal is for

incremental, not alternative debt financing, as specified under the merger

agreement.” As Hexion explained in a

manner that belies the conditional relief sought in this action: “We are not seeking to renegotiate this

transaction. We are

seeking to terminate it.” See App. Tab N: DX-2384 (emphasis added).

Rather than pursuing constructive

alternatives to help close the merger as Hexion is contractually obligated to

do, Apollo and Hexion have created this façade of seeking alternative financing

that was designed to fail.

ARGUMENT

I. HEXION’S

FAILURE TO CONSUMMATE THE FINANCING AND MERGER ON THE GROUNDS OF “INSOLVENCY”

WOULD CONSTITUTE A BREACH OF HEXION’S COVENANTS UNDER THE MERGER AGREEMENT.

Hexion’s “insolvency” argument bears little

relationship to the actual terms of the Merger Agreement. For several months, Plaintiffs have been

trying to show insolvency, apparently in hopes that no one will notice the

insolvency “out” they are trying to substantiate does not even exist in the

Merger Agreement. On its face, the

Merger Agreement provides virtually no basis for Hexion to get out of the

merger (aside from an extraordinarily tight MAE clause). The context in which the Merger Agreement was

negotiated shows why this is so.

Huntsman had a great deal of leverage in the contract negotiations

because it already had in hand a signed, tight deal with Basell. Based on Huntsman’s own experience with Apollo

and knowledge of Apollo’s

19

reputation, Huntsman was extremely concerned

to ensure that any contract with Apollo provided a certainty of closing. Huntsman demanded, and Hexion agreed to,

unprecedented and restrictive terms in the Merger Agreement, reducing to a

vanishing point any optionality for Hexion in the deal.

In the Merger Agreement, there is no

financing “out” for Hexion. On the

contrary, Hexion represented and warranted to Huntsman that it had sufficient

financing for the transaction. App.

Tab A: JX-1, § 3.2(e). The Merger

Agreement requires Hexion to use reasonable best efforts to do, or cause to be

done, all things advisable, necessary, and proper to consummate the Commitment

Letter financing and the Merger. Id., §§ 5.12(a), 5.13(a).

If there is any problem with financing, the Merger Agreement does not

provide Hexion with an excuse to get out of the Merger. Instead, it triggers Hexion’s obligation to

try harder to obtain financing, or face nearly unlimited liability for a

knowing and intentional breach under section 7.2(b) of the Merger

Agreement.

Nor does the Merger Agreement provide Hexion

with an “insolvency” out or anything remotely resembling one. The only two provisions in the Merger

Agreement relating to solvency are expressly for the benefit of Huntsman and

are waivable by Huntsman. First, in Section 3.2(k) Hexion

represented and warranted to Huntsman that the Surviving Corporation (which,

under the Commitment Letter, would guarantee approximately $16 billion of the

Combined Entity’s debt) would be solvent at Closing under each of three

solvency tests. Second, pursuant to Section 5.13(f),

Hexion is required to provide to Huntsman a third-party solvency opinion prior

to Closing. Hexion is bound by these

contractual representations and undertakings and thus cannot be heard to argue

to the contrary in this litigation. See Vitalink Pharm. Servs. v. GranCare, Inc., 1997 Del.

Ch. LEXIS 116, *32 (Del. Ch. Aug. 7, 1997) (because of contractual

agreement that a breach would result in substantial and irreparable harm to the

plaintiff,

20

defendant could not assert a contrary

position in litigation); SLC Beverages, Inc.

v. Burnup & Sims, Inc., 1987 Del. Ch. LEXIS 472, at *6

(Del. Ch. Aug. 20, 1987) (same).

If there are any potential problems or issues

with solvency, the Merger Agreement requires Hexion to exercise its reasonable

best efforts to fix them. Under the

Merger Agreement, Hexion is required to exercise its reasonable best efforts to

fix any potential problems or issues with solvency. Hexion is obligated to (i) use its best

efforts to take all actions and do all things “necessary, proper or advisable

to” arrange and consummate the merger and the financing, (ii) not take any

action to impair its own ability to satisfy this obligation or Huntsman’s

ability to do so, (iii) keep Huntsman informed with respect to all “material

activity” regarding financing and any efforts regarding the requirement to

deliver a solvency opinion or appropriate certificate, and (iv) notify

Huntsman within two business days if Hexion “no longer believes in good faith

that it will be able to” deliver a solvency certificate or obtain a solvency

opinion.

Hexion attempts to manufacture a solvency

issue between it and Huntsman by referring to the Commitment Letter, to which

Huntsman is not even a party. Contrary

to Hexion’s assertion, the non-occurrence of a condition to the banks’

obligation to fund under the Commitment Letter does not excuse Hexion’s

performance under the Merger Agreement.

The risk that financing might not be available, or might not be

available from a particular source, was a risk expressly allocated to Hexion in

the Merger Agreement.

Moreover, even the Commitment Letter does not

condition the banks’ obligation to fund based on the solvency per se of the Combined Entity. To avoid the risk that Hexion might frustrate

consummation of the merger by refusing to certify solvency, Huntsman required

that the banks’ obligation to fund could also be satisfied by the delivery of a

solvency certificate or opinion from (i) Huntsman’s CFO, or (ii) Hexion’s CFO, or

(iii) a reputable valuation firm.

App. Tab B: JX-219, ¶ 6.

Notably, there is no requirement that all three, or even two of the

21

three, concur in the solvency

determination. The parties and the banks

have agreed that the Huntsman CFO or a reputable valuation firm can certify

solvency. Thus, this Court is not

required to decide the question of solvency because the evidence presented at

trial will overwhelmingly demonstrate that Hexion’s assertions of insolvency

are a sham and that a solvency certificate or opinion can be delivered.

Because Hexion alleges that insolvency is a

proper ground for avoiding its obligations under the Merger Agreement and seeks

declaratory relief on this basis, Delaware law places the burden to prove

insolvency on Hexion. See Frontier Oil Corp. v. Holly Corp., No. Civ. A

20502, 2005 WL 1039027, at *34-35 (Del. Ch. Apr. 29, 2005) (holding that

party seeking to avoid contractual obligations based on an alleged occurrence

of an MAE had burden to prove MAE); In re IBP, Inc.

Shareholders Litig., 789 A.2d 14, 53 (Del. Ch. 2001) (same); Energy Partners, Ltd. v. Stone Energy Corp., No. Civ.

A. 2402-N, 2006 Del. Ch. LEXIS 182, at *21 n.55 (Del. Ch. Oct. 30, 2006) (“a

plaintiff in a declaratory judgment action should always have the burden of

going forward”); Rhone-Poulenc v. GAF Chems., No. Civ.

A. 12,848, 1993 Del. Ch. LEXIS 59, at *6 (Del. Ch. Apr. 6, 1993) (“The

usual rule is that the burden of persuasion in a civil action rests upon

him who makes the allegations.”).

Plaintiffs cannot meet their burden.

A. Hexion Is Not Excused from Its Contractual Obligations Based

on D&P’s “Insolvency Opinion” Because Hexion Has Not Used Its Reasonable

Best Efforts To Satisfy the Conditions of the Commitment Letter and Has Failed

To Keep Huntsman Apprised of Material Events.

Under the Merger Agreement, financing is not

a condition to Hexion’s obligation to consummate the merger. Nevertheless, Hexion represented that Apollo

had received the Commitment Letter, that the Commitment Letter was “in full

force and effect,” and that the proceeds contemplated by the Commitment Letter

were sufficient to pay the amounts due at closing:

22

The aggregate proceeds contemplated to be

provided by the Commitment Letters will be sufficient

for Merger Sub [Hexion’s subsidiary created to consummate the merger] and the

Surviving Corporation to pay the aggregate Merger Consideration . . . , the

Aggregate Option Consideration, any repayment or refinancing of debt

contemplated in the Commitment Letter and fees and expenses of [Hexion], Merger

Sub and their respective Representatives incurred in connection with the

Transactions (collectively, the “Required Amounts”).

App. Tab A: JX-1, § 3.2(e) (emphasis

added). To cement the concept that

financing was Hexion’s sole risk and obligation, the Merger Agreement does not

allow Hexion to terminate for failure to obtain financing.

1. The Merger Agreement Imposes Stringent Obligations on Hexion

To Consummate the Merger.

Hexion covenanted in the Merger

Agreement to use “reasonable best efforts” to take all actions and do “all

things “necessary, proper, or advisable” to consummate the financing

contemplated by the Commitment Letter (known as the “Financing” under the

Merger Agreement) and to consummate the Merger Agreement. Section 5.12(a) imposes this

requirement on Hexion with respect to consummating financing and satisfying the

terms, covenants, and conditions in the Commitment Letter.

[Hexion] shall use its reasonable best efforts to take, or cause to be

taken, all actions and to do, or cause to be done, all things necessary, proper

or advisable to arrange and consummate the Financing . . . , including . . .

using reasonable best efforts to . . . satisfy on a timely basis all terms,

covenants and conditions set forth in the Commitment Letter.

App. Tab A: JX-1, § 5.12(a).

Section 5.13(a) imposes

this obligation on Hexion to consummate and make effective both the financing

and the merger.

Except to the extent that the parties’

obligations are specifically set forth elsewhere in this Article V,

.. . . each of the parties shall use reasonable

best efforts to take, or cause to be taken, all actions, and to do,